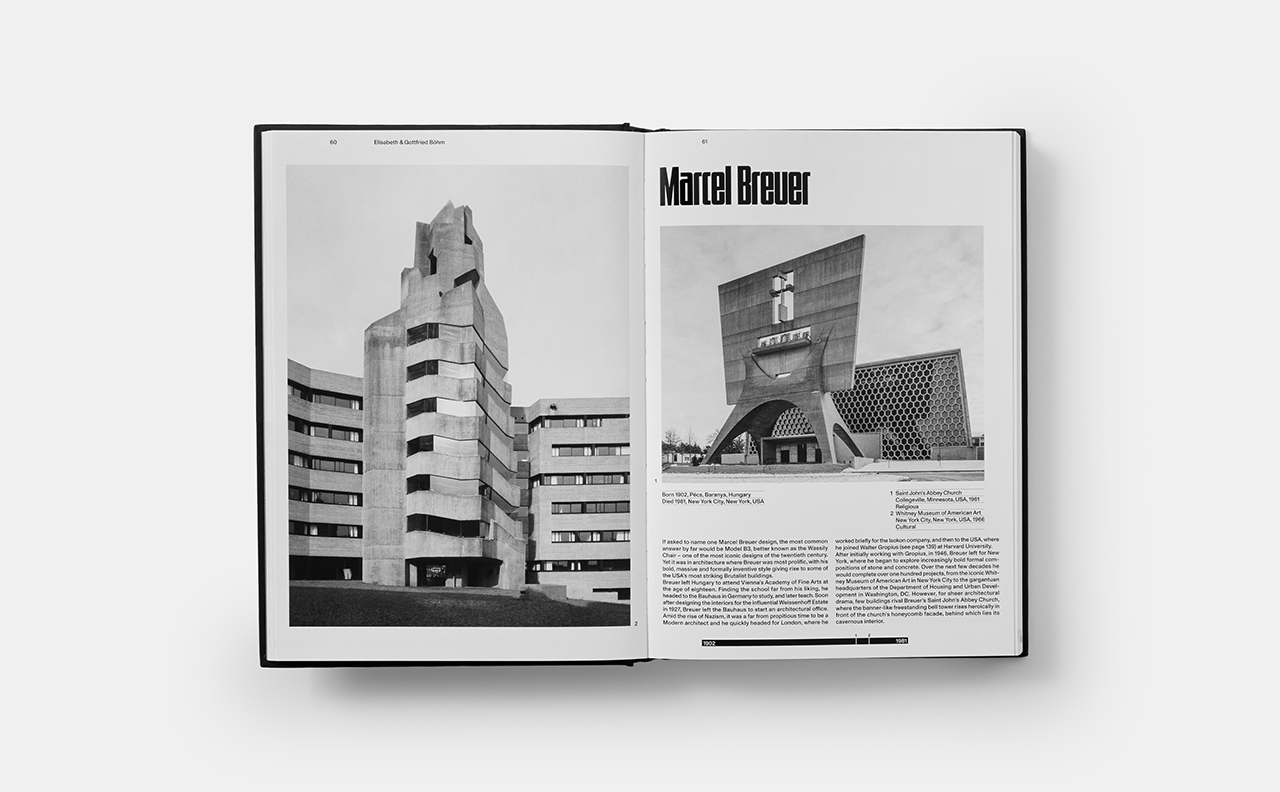

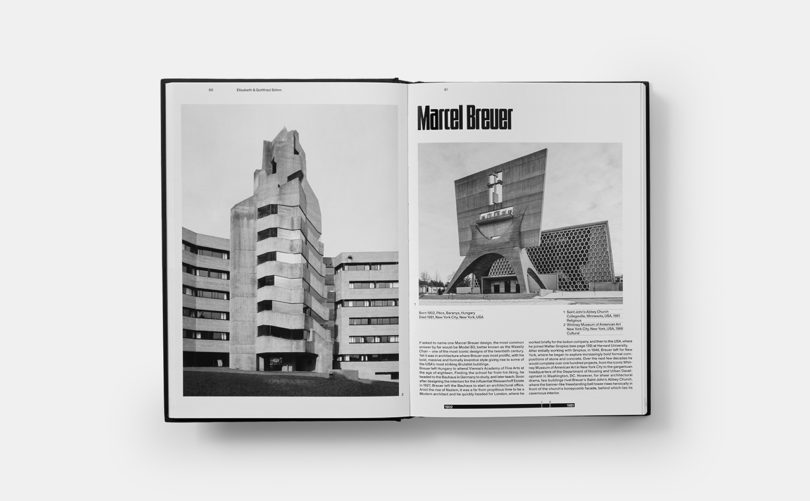

If there’s one thing we can all agree on when it comes to Brutalism, it’s that it’s unquestionably divisive. Since its inception in 1936, people have either loved or loathed the architectural style with very little grey space in between. What can’t be denied is that the style has produced some of the world’s most interesting buildings.

Author Owen Hopkins has taken on the task of whittling down a list of Brutalist architects to highlight in The Brutalists: Brutalism’s Best Architects, published by Phaidon. That number is somewhere north of 250 individuals, with each profile including selected samples of their work and a short biography/introduction. From international icons to lesser known or neglected Brutalist architects, Hopkins has created a written record of the global movement.

Warren & Mahoney, Christchurch Town Hall, Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand, 1972 \\\ Photo: Warren and Mahoney Architects (page 328) Maurice Mahoney, Miles Warren

During the year it took Hopkins to research and write “The Brutalists” he realized just how pertinent the school’s ideology remains today. “The Brutalists believed that architecture had the power to remake the world for the better,” he said. “Given the myriad challenges we face collectively as a society, it’s an ambition we urgently need to recapture.”

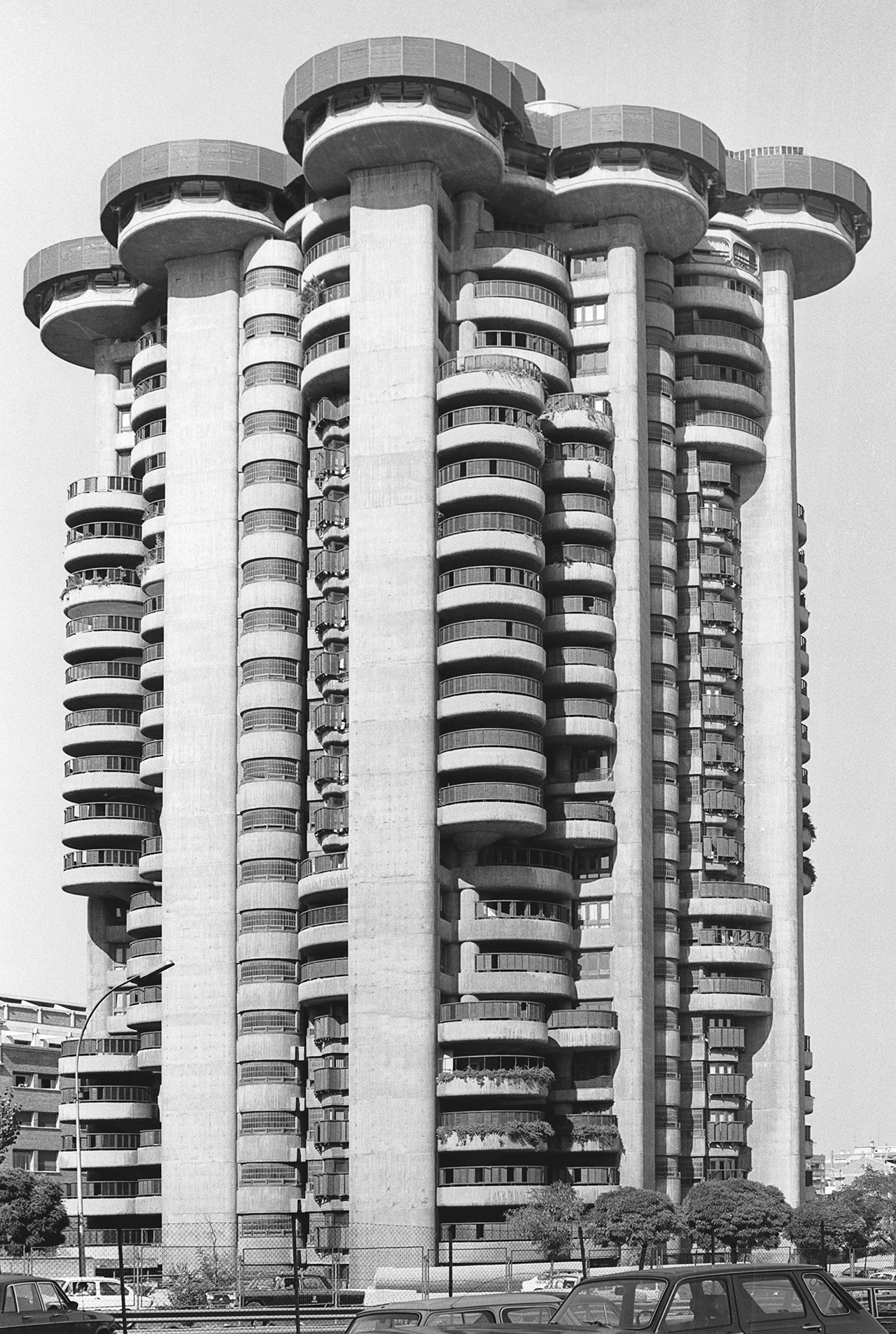

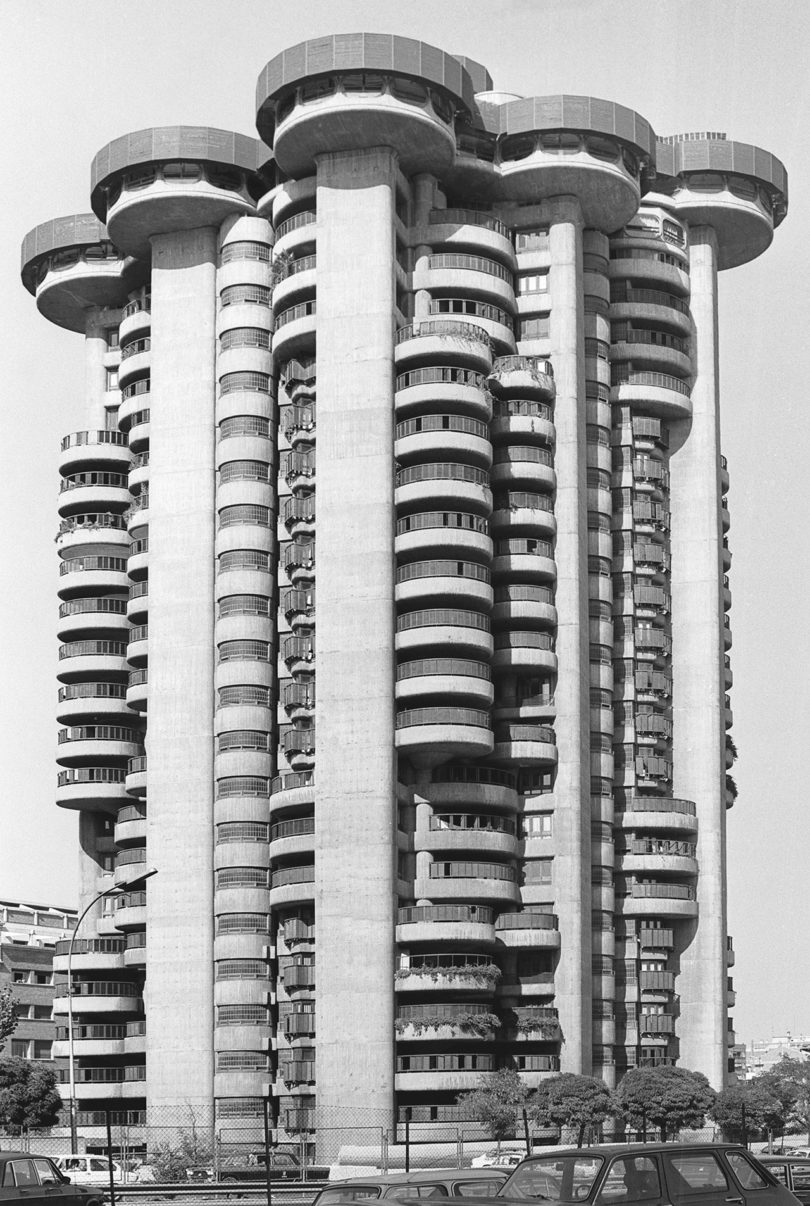

Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza. Torres Blancas, Madrid, Spain, 1969 \\\ Photo: Javier Sáenz, Guerra (page 275)

“It’s the sense of ambition, the idea that architecture can act as a synthesis of massive, competing, and often contradictory forces” that draws Hopkins in. “Brutalism was often overambitious, hubristic, or simply misguided, but, wow, you have to admire the bloodymindedness and sheer force of will.”

Bogdan Bogdanović. Shrine Dedicated to Serb and Albanian Partisans, Mitrovica, Kosovo, 1973 \\\ Photo: © Roberto Conte, @ilcontephotography (page 56)

After being immersed in a subject it would be near impossible to come away without a favorite, and for Hopkins that’s architect Louis Kahn. “Some people wouldn’t actually class him as a Brutalist, and it’s certainly true that he does evade conventional labels and in a way stands alone in the history of twentieth-century architecture. But for me, it’s in his work where the paradoxes of Brutalism (which I explore in the introduction) are most apparent,” he shared. “His work has an amazingly timeless quality yet is also inextricably tied into its historical moment. His buildings employ an almost universal architectural language, all massive abstract shapes and forms, but they are also embedded in their locations; there’s this massive, elemental quality to his work, yet at the same time there’s this amazing finesse and tactility to it. Architecture, for Kahn, was an almost spiritual thing, taking us to the heart of what makes us human.”

Of course, if one has a favorite Brutalist architect they also likely have a favorite structure – though not always designed by the same person, as Hopkins exhibits. “I do have a soft-spot for the work of Owen Luder, not because it was always very good or well-built (frequently it wasn’t) and much of it has been knocked down,” he noted. “A lot of commercial architecture plays it safe, but not Luder’s work. This was architecture that ran the full gamut in attempting to create buildings distinctive to their locations. It frequently didn’t work and they became distinctive for the wrong reasons. But in the case of the Trinity Square Carpark just across the river from where I am in Newcastle, UK, you just have to look at the banality of the development that replaced it to long for the raw power of Luder’s work.”

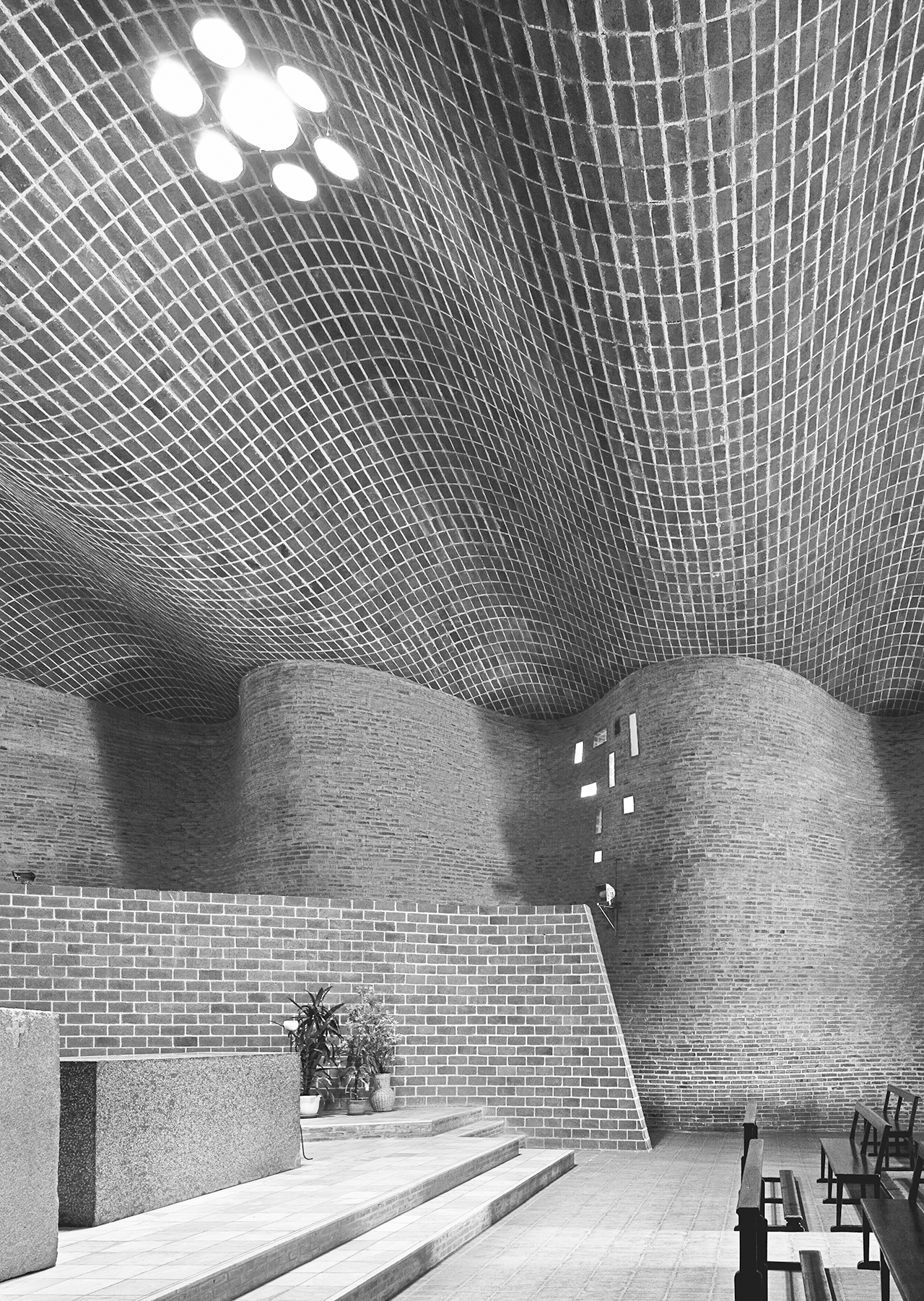

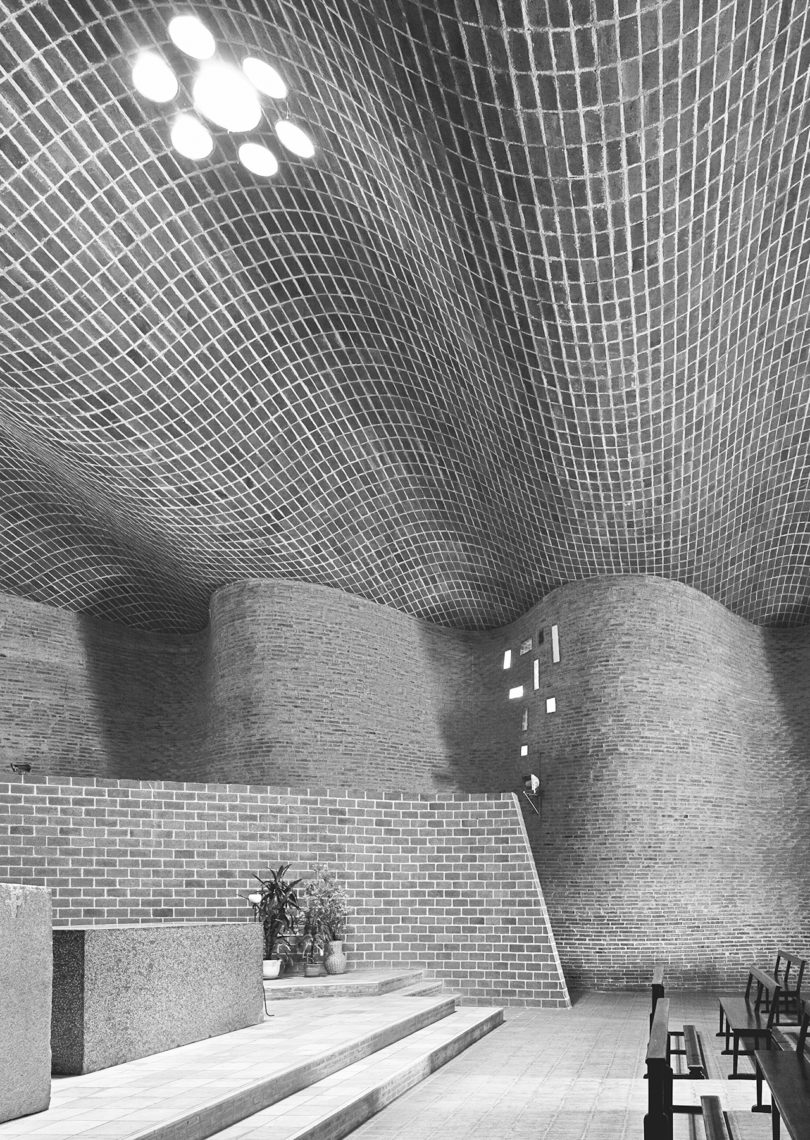

Eladio Dieste. Church of Christ the Worker, Atlántida, Canelones, Uruguay, 1958 \\\ Photo: Leonardo Finotti (page 96)

A lesser-known Brutalist architect who left a lasting impression on Hopkins during his research is Högna Sigurðardóttir. She’s “well-known in her native Iceland, but much less so internationally. I have to confess not being aware of her work until starting on the book,” he said. “Although I haven’t visited them (yet!) the series of houses she designed in the 1960s are extraordinary in their massing, their relationship to the ground, and their unsparing attention to detail. She managed to design houses that are works of art, yet also wonderful family homes.”

Igor A. Vasilevsky, Druzhba Sanatorium, Kurpaty, Yalta, Ukraine, 1985 \\\ Photo: Frederic Chaubin (page 323)

In all, the book includes images of more than 200 iconic Brutalist buildings from 1936 to the present day, gifting us with a massive volume of talent from the masters of the style. Pick up your own copy here.