Stockholm-based Martin Thübeck graduated with a master’s degree in Spatial Design from Konstfack University College of Arts, Crafts and Design in 2020. His Betula Collection features a frame made from identical pieces of reclaimed wood, connected by a single joint. For the chair, rawhide rejected by the leather industry is dried around the frame to hold it in place, while a dresser features cord – both designed for disassembly.

Tell me a little bit about your childhood, education, and background in terms of how you first became interested in creativity, design, and sustainability.

For as long as I can remember I have loved to draw, paint, and create things with my hands. The ability to materialize my imagination gave me a strong sense of freedom and acted as a catalysator to imagine even more. My constant creativity landed me a middle spot in a school with a focus on art and design. During these years I spent a lot of time painting and as my skill grew, the pressure to continue that path only got bigger. When it was time to decide on a direction for senior high school, I was offered a spot at a prestigious art school, but the pressure from all the years made me rebel and apply instead for an education in cabinet making. A much less prestigious and more pragmatic direction, but something I longed for at the time. There, I found it very rewarding to have an artistic background when learning carpentry. I work for many years with carpentry before the passing of my mother made me apply to Konstfack, where I fully explored my pragmatic and artistic side. The education has a strong focus on sustainability and today forms the backbone of all my projects.

How would you describe your project/product?

The Betula project is a collection of furniture made from the waste generated by a Swedish birch sawmill. It is a reaction to the part of modern forestry that people tend not to see – and how the material’s origin is generating a lot of waste. In the project, I have experimented with the power of the single building block and how modularity can prolong the lifespan of furniture.

What inspired this project/product?

The project started out as an investigation into how Swedish forestry has evolved over the past hundred years and how this is affected by climate change. Sweden is one of the world’s largest exporters of forest-based products and this has affected how the Swedish forests look today, the majority of which have been planted. Today only 20% of the trees are ‘leaf trees’ as the biggest profits have been found in pine and spruce, which can be planted closer together. With the rapid change in climate it has become evident that these planted forests are very vulnerable to storms, pests, and fires. To prevent this there is a need for much more biodiversity of the sort you would see in ancient natural forests.

This made me interested in the third most common tree in Sweden, Birch. Birch constitutes 12% of the total Swedish forestry and is the most common leaf tree. To get an image of the birch industry I visited one of Sweden’s biggest Birch sawmills. Their clients expect only the best quality with as straight fibers as possible – and a pale color at odds with the natural reddish color Birch often displays naturally. In order for the sawmill to compete, the owner of the sawmill explained that roughly 70% of all the logs that come into the facility are considered waste and burnt. The way the production line is set up, all material goes through the entire refining steps and then gets sorted before the drying process. If something goes wrong in the drying process this can also discolor the wood and render it useless for the furniture industry.

What waste (and other) materials are you using, how did you select those particular materials and how do you source them?

At the sawmill, I saw giant piles of waste material that only have minor variations from the desired standard, that sometimes weren’t even visible. These piles inspired the idea to explore how the least amount of work could affect the value of the discarded material the most. By using the dimension of the material and only altering their ends, finding a simple joint that could fit both into itself in several ways and also join along the pieces. The result was to mill a cut one-third of the thickness and as deep as the widest profile of the material.

When did you first become interested in using waste as raw material and what motivated this decision?

Unfortunately, waste is such a widely accessible material, so I started using it long before I even understood the concept. As I got older, I started to question things more and I enjoyed showing the potential in the unwanted. When I started to study design and learning more about sustainability, the concept of using waste came very naturally.

What processes do the materials have to undergo to become the finished product?

In this project, I wanted to explore how the least amount of work could affect material the most. The pieces are only cut in length and a groove is milled in either end, creating a ‘tongue and groove’ joint except that the tongue is the thickness of the material and the groove is the cut in the end of the material.

What happens to your products at the end of their life – can they go back into the circular economy?

I found inspiration in Gerrit Rietvelds ‘Krat’ system where he took inspiration from an object which denotes other functions, such as a packing case. And Enzo Maris ‘Autoprogettazione?’ project where he wanted to educate consumers about design. In both these projects, nails held the boards together. I wanted to explore if I could find a more flexible alternative way to hold the structures together – experimenting with paper cord and rawhide.

Close to the sawmill is a tannery and leather is a material that also has strong visual preconceptions and expectations. When visiting this tannery, I learned that a lot of the hides that come from the slaughterhouse have scares, mosquito bites and other defects that will show after the tanning process. These hides or parts of hides will then be considered waste.

Wood and leather have a long history of being used together. Instead of traditional upholstering I let the soft hide dry and shrink around the wood structure of the Betula chair making it sturdy and strong.

This was a way of prolonging the life of these pieces as they can be separated and put back together as something else.

How did you feel the first time you saw the transformation from waste material to product/prototype?

I think my first reaction was surprise at how little work could change the value so much. It went from being waste to a building block that I instantly started playing around with trying to figure out what to build. This process is still ongoing and the furniture collection is slowly growing.

How have people reacted to this project?

Due to the pandemic, the project has not been shown in its entirety but the few times I have had the possibility to show it, I have tried to engage people in the building possibilities. This way people have touched and reflected on the material in a much deeper way. Hopefully, the project can be shown soon and to be experienced, so more can learn about the potential in the unwanted.

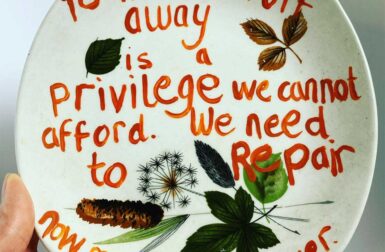

How do you feel opinions towards waste as a raw material are changing?

I believe more and more people see the potential, not only financially but also the necessity if we want to continue to inhabit this planet. I find hope in the growing number of projects showing ways of moving towards a more sustainable way of living.

What do you think the future holds for waste as a raw material?

I hope that we soon stop viewing anything as waste and start to see everything as potential raw materials.